Based on performance and ability alone, Kenny Washington should have joined the NFL in 1940.

At UCLA, where he played in the backfield alongside Jackie Robinson, he led the nation in total offense in 1939, with 812 rushing and 559 passing yards, and won praise as one of the nation’s best. (He also excelled at baseball, which he later described as his “first love.”)

Selected to play in a 1940 all-star game in Chicago that pitted the best college players against the NFL champion Green Bay Packers, Washington scored a touchdown and impressed George Halas, the legendary owner and coach of the NFL’s Chicago Bears.

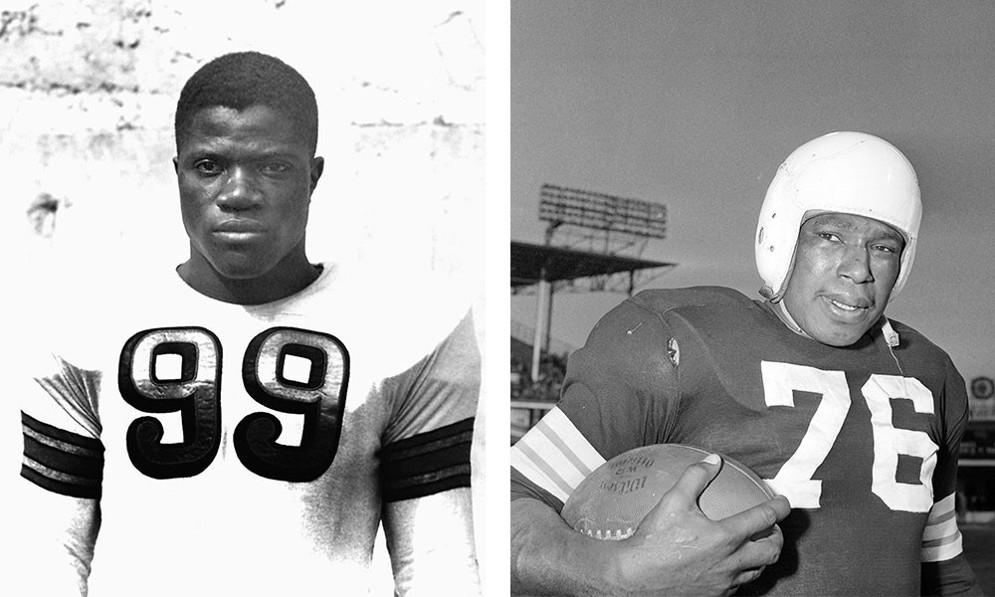

Kenny Washington led the nation in total yards in his senior year at UCLA in 1939, but had to wait seven years for the opportunity to play in the NFL. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

That didn’t lead to an NFL contract for Washington, though: Seven years earlier, NFL owners had informally agreed to ban black players. By many accounts, Washington stayed in Chicago after the game at Halas’ behest while Halas tried unsuccessfully to persuade the other owners to lift the ban.

Instead of playing for the NFL, Washington joined the Los Angeles Police Department and played for the Hollywood Bears, a semi-pro team in the Pacific Coast League. One of his teammates there was another black player, Woody Strode, who had starred at UCLA as a receiver.

A breakthrough would not come until 1946, when Cleveland’s NFL team, the Rams, moved to Los Angeles and sought a lease to play at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. At the same time, a team from a rival league, the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), also applied to play there. Under pressure from the Coliseum Commission and black sportswriters — football historians give Los Angeles Tribune sports editor Halley Harding particular credit — both the NFL’s Rams and the AAFC’s Dons announced their intent to integrate as a condition of their leases.

The Dons stalled and didn’t sign a black player until 1947. Harding and others pressured the Rams into signing Washington in March 1946. A short time later, the Rams also signed Strode.

That same year, in the AAFC, Paul Brown, coach and part-owner of its Cleveland franchise, voluntarily sought and signed two other black standouts, Bill Willis and Marion Motley. (Brown had coached Motley at Naval Station Great Lakes, and Willis at Ohio State.) Over the years leading up to its 1950 merger with the NFL, the AAFC would outpace the NFL on integration, further increasing pressure on the NFL to open its doors of opportunity.

Hall of Famers Bill Willis, guard, and Marion Motley, back, both of the Cleveland Browns. (AP Photo/File) (AP Photo/Harry Hall)

The four 1946 signings came a year before Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier — and in terms of abuse, reintegrating pro football may have been more daunting. In a game where contact is expected, the players endured some brutal physical treatment on the field, as well as verbal abuse off it.

Pro football’s reintegration may be less remembered than Robinson’s historic breakthrough, though, because baseball — the “national pastime” — was the country’s most popular sport then. Baseball also had kept blacks out of the game for much longer; while only a handful of black players had been in the NFL before 1933, they included trailblazers such as Frederick “Duke” Slater, who played from 1922 to 1931, and Fritz Pollard, who played and coached from 1920 to 1928.

After those 1946 signings, the NFL’s reintegration progress was slow. But by 1959, black players accounted for about 12 percent of NFL rosters, Sean Lahman wrote in his 2008 book, “The Pro Football Historical Abstract.”

“The democratic idealism sparked by World War II, the protests of writers and fans, the emergence of the AAFC, and the success of several minority athletes in college football all account for the collapse of professional football’s racial barrier,” Nichols College history professor Thomas Smith wrote in 1988 in the Journal of Sport History.

Over time, other racial barriers in the NFL fell. Nearly 20 years after reintegrating, the league hired its first black official, Burl Toler, in 1965. Black quarterbacks became widely accepted in the 1980s – although Pollard played the position in the 1920s and Willie Thrower re-broke the barrier in 1953 when he threw eight passes in one game for the Chicago Bears. In 1989, the Los Angeles Raiders made Art Shell the league’s first black head coach since Pollard in the mid-1920s.

Washington, who had undergone numerous knee operations before joining the league, lasted only three years before retiring because of his physical ailments. But he did finish fourth in rushing yards in 1947, averaging 7.4 yards per carry, and set a Rams record that stands to this day with a 92-yard run.

Strode was let go after one season, moving on to a short stint in the Canadian Football League and spending time as a professional wrestler before embarking on a successful acting career.

Motley and Willis had Hall of Fame careers with the Browns, one of three AAFC teams to join the NFL when the leagues merged in 1950. In nine professional seasons, Motley amassed 4,720 yards on just 828 carries, for a 5.7 yards-per-carry average that still ranks among the highest of all time. Willis, renowned for his lightning quickness as a defensive middle guard, played through 1953.

Together, from 1946 to 1953, they helped lead the Browns to four AAFC championships and one NFL championship, as well as three additional NFL championship games.

Whatever their accomplishments on the field, Washington, Strode, Willis and Motley forever changed professional football. In his Journal of Sport History article, Smith cited the enthusiasm of one black sportswriter, who wrote in 1947: “The limitations have been lifted and, now, the sky’s the limit.”

The NFL, of course, is far better for it.