Evolution of the NFL Player

Creating an NFL player: from “everyman” to “superman.”

Creating an NFL player: from “everyman” to “superman.”

Their lives didn’t revolve around the game. It was common for players to “job in” for weekend contests, which didn’t allow for practice time with their teams. Their pay made them “professional” by definition, but with a laxity to the term that would not apply today.

The game and the players changed over time as the rules changed, and as the league became more competitive, popular and prosperous.

Today, only football’s elite players get to the NFL, and they are very well-compensated: the average contract at the start of the 2017 season was $2.25 million. Competition for roster spots is fierce, with fewer than 1 percent of all college football players earning a roster post at the game’s highest level.

Most players are bigger and stronger — particularly offensive and defensive linemen, whose size and weight surpass the average man's. And players are more specialized by position, with physical attributes and customized training rituals unique to their roles.

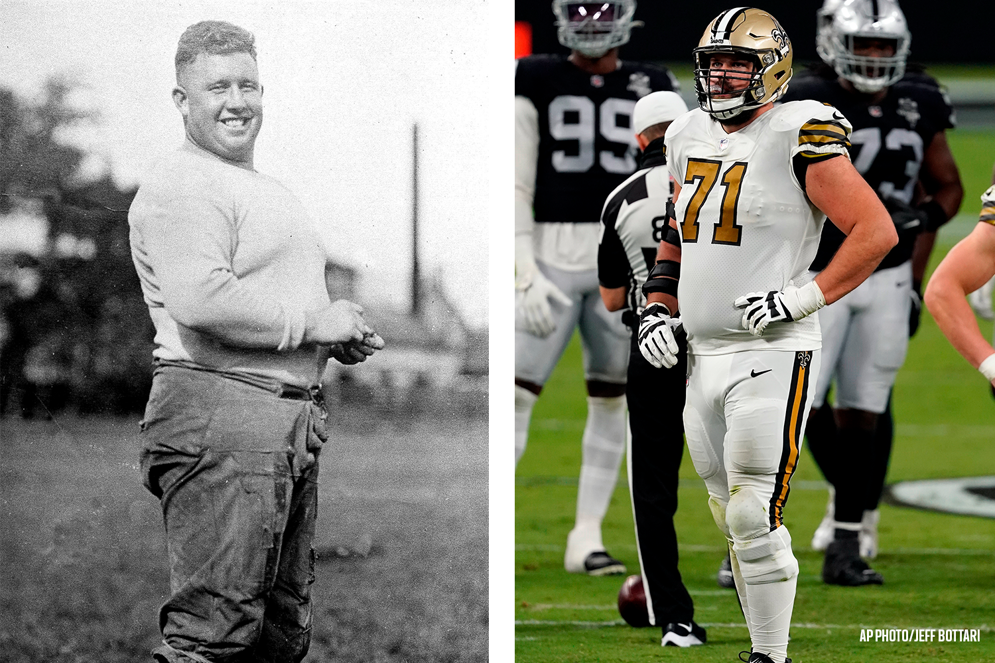

Hall of Famer Wilbur “Pete” Henry, aka “Fats,” was one of the NFL’s largest and most dominant linemen in the 1920s at 5 feet 11 inches and 245 pounds, but would be dwarfed by present-day players such as 6 foot 6 inch, 313-pound New Orleans offensive tackle Ryan Ramczyk. (Pro Football Hall of Fame) (AP Photo/Jeff Bottari)

As players progress from high school through the pros, they’re increasingly supported, coached and counseled by trainers, nutritionists and medical staff that prepare them for peak performance on gameday and help them recover from injury. Their training and preparation often continues through the offseason.

NFL players are professionals in every sense of the word, well-paid and well-trained students of the game whose lives revolve around football. The league, in turn, surrounds them with resources to help them become the best they can be. But it all had to start somewhere — in this case, with a man named William “Pudge” Heffelfinger.

On Nov. 12, 1892, Heffelfinger received $500 in cash for playing in a football game. There may have been others before him, but a document unearthed by the Pro Football Hall of Fame nearly 80 years later provided the first irrefutable evidence of a person being paid to play. Heffelfinger posthumously earned the status as the country’s first professional football player.

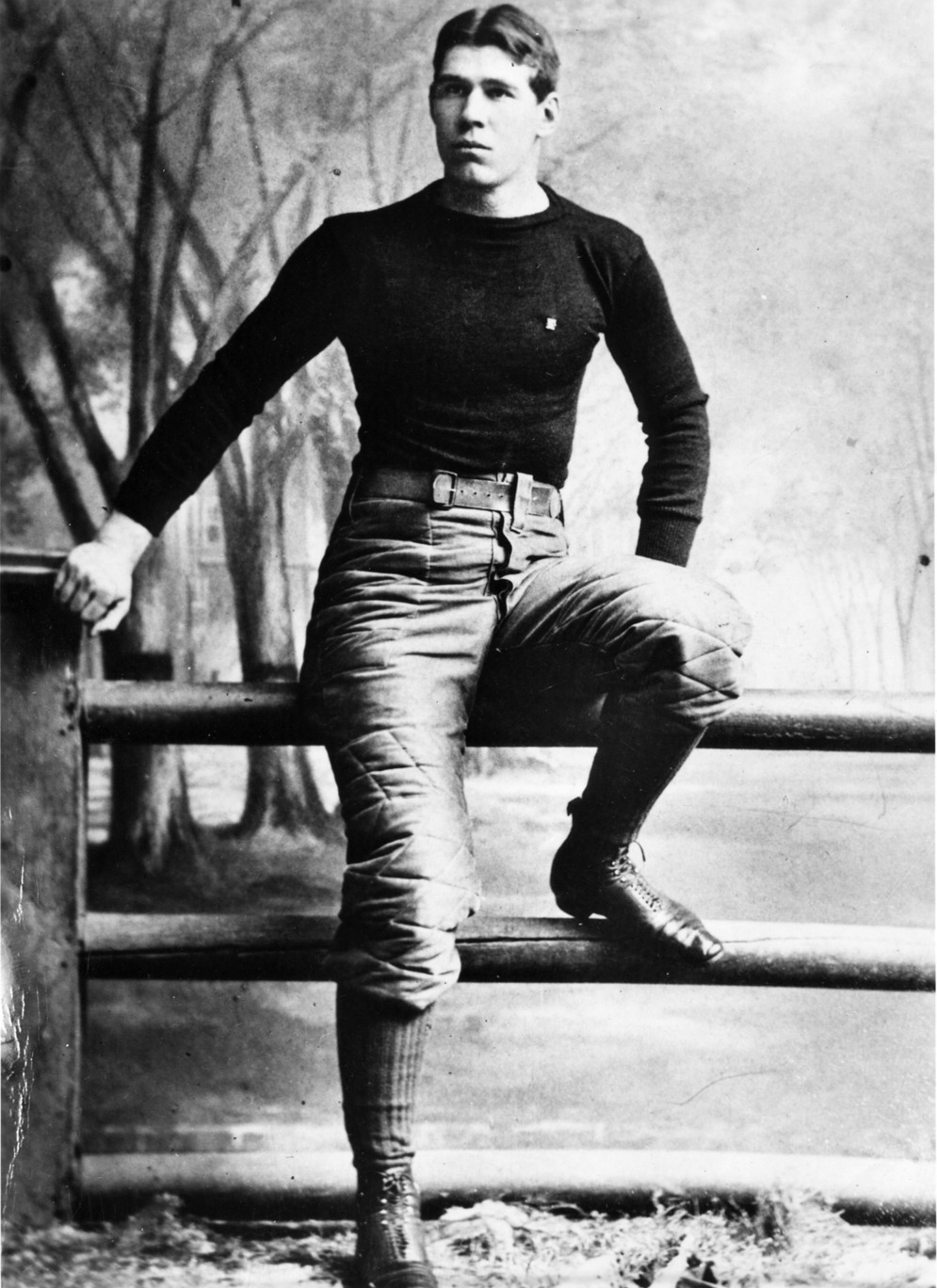

At 6 feet 3 inches tall and 200 pounds, William “Pudge” Heffelfinger “was especially big for that era and towered over his opponents,” according to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

At the time, all football players were supposed to be amateurs — many of them playing for teams created by the athletic clubs that sprang up across the country after the Civil War. With the competition between clubs becoming more intense, many tried to circumvent the restriction by finding jobs for their stars, awarding players expensive trophies or watches that they could pawn, or doubling their expense money. But none of them paid cash, at least not openly.

A Nov. 12, 1892, contest between Pittsburgh-area rivals the Allegheny Athletic Association and the Pittsburgh Athletic Club changed everything. As the game approached, both teams were determined to beef up their squads. Heffelfinger — a low-salaried railroad office employee in Omaha, Neb. — became one of their targets.

The clubs had good reason to bid for his services. As a football All-American at Yale from 1888 to 1891, Heffelfinger was considered one of the sport’s best linemen. According to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, “his size allowed him to wreak havoc on opposing lines, where it was said he would typically take out two to three players at a time.” He helped lead Yale to two undefeated and two one-loss seasons (including one incredible undefeated campaign in which it outscored its opponents 698-0).

Heffelfinger’s post-college status, however, was typical for football’s rag-tag days. He went to work at the railroad, but continued playing for independent teams. In the weeks before the Allegheny-Pittsburgh contest, he took a leave of absence from the job to take part in a six-game tour of the East with the Chicago Athletic Association, which used the expense-money method to attract players.

The Pittsburgh Athletic Club scouted one of those games and, according to a Pittsburgh Press story at the time, offered Heffelfinger $250 to play for them on Nov. 12. Allegheny offered him $500. The star played for Allegheny and earned his keep by forcing a fumble, scooping it up and racing for a touchdown — the game’s only score.

Allegheny did not admit to paying Heffelfinger at the time, but the Hall of Fame discovered a club expense sheet that shows the $500 transaction. It calls the document “pro football’s birth certificate.”

Allegheny shelled out $250 for a different player in a Nov. 19 game, and for the 1893 season, it signed three players to contracts that promised them $50 per game. The pay-to-play model had arrived.

The six Nesser brothers, known for their overpowering play, averaged more than 210 pounds in an era where the average professional lineman weighed 180. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

The payments, however, were not high enough to induce dramatic change. In the early 1900s, without the developmental pipeline that exists today, pro football players still came from virtually anywhere. For many, their strength came from hard labor, not football-specific training or college play.

One of the game’s toughest and most popular teams of that era emerged from the sandlots and railroad yards of Columbus, Ohio, where six outsized brothers built their muscle through backbreaking work and played football during lunch breaks.

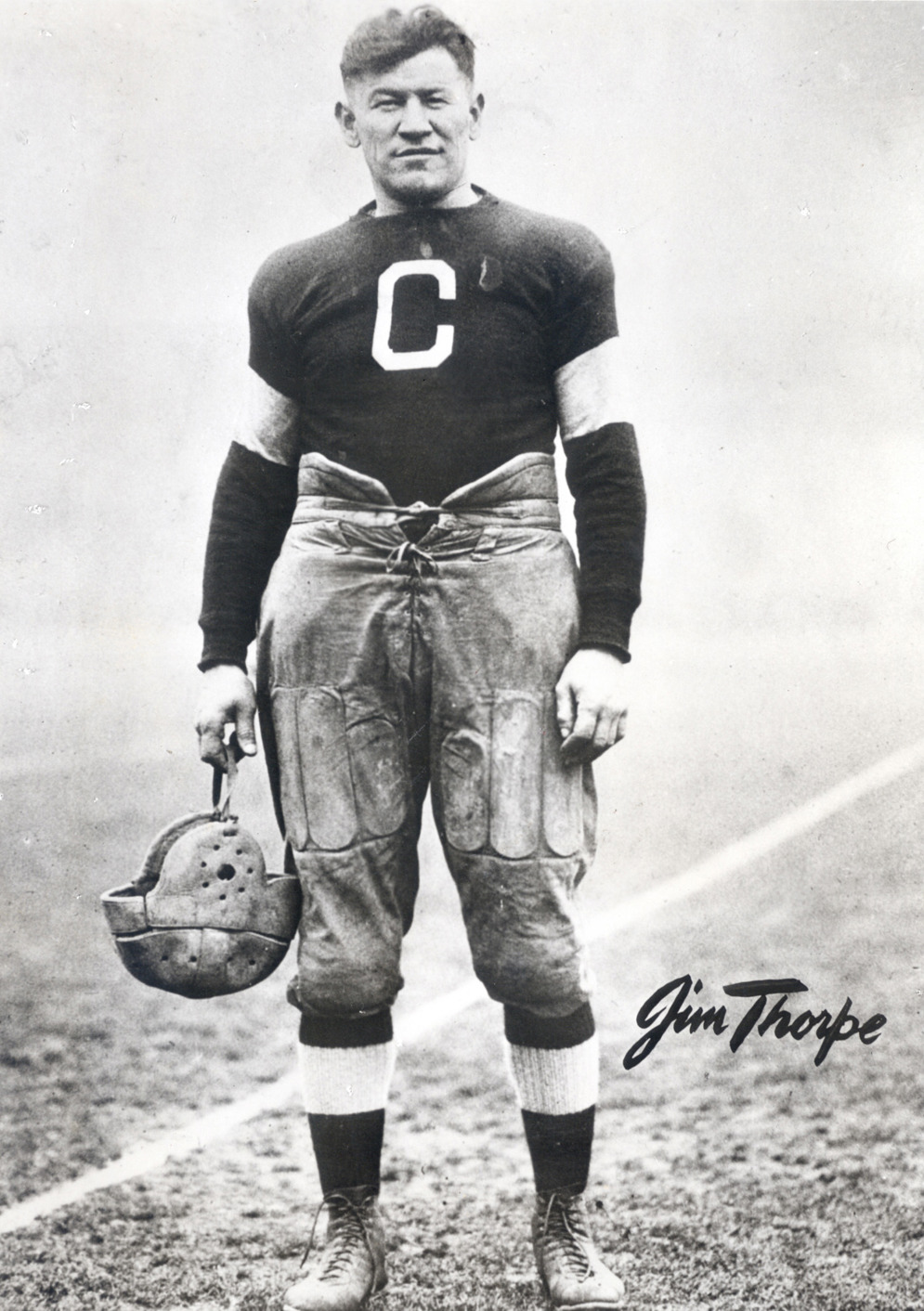

Jim Thorpe, 6 feet 1 inch tall and about 200 pounds, combined speed with bruising power as a halfback. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

Joe Carr formed the Columbus Panhandles in 1907, with the Nesser brothers as the nucleus. Renowned for its bruising play, the team would become a big road game draw as the “most famous football family in the country,” the Hall of Fame says.

Jim Thorpe — the 1912 Olympics decathlon and pentathlon gold medalist — became an even bigger attraction for the fledgling sport than the Nessers.

Signed by the Canton Bulldogs in 1915 for the then-princely sum of $250 a game, Thorpe already had proven his football mettle by earning first-team All-American honors in 1909 and 1910 while playing college football for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. He also played professional baseball. Having such an elite and high-profile athlete boosted the sport’s prestige.

In 1920, both the Panhandles and Bulldogs became charter members of the 14-team American Professional Football Association, which changed its name to the National Football League in 1922.

The league appointed Thorpe as its first president. Carr became its second in 1921 and held the position for 18 years; as one of his first actions, he established a standard player contract modeled on the one used in baseball.

The formation of the league would be looked back on as a seminal moment for pro football, of course, but also for players. Over time, the league would provide a structure for player recruitment and development, as well as the rules and conditions that would shape how the game is played and who plays it.

By 1920, college football had begun to demonstrate its superiority as a source for pro players, completing a shift that had begun with Thorpe in 1915.

“The day when a whole team of rugged sandlotters could compete on an equal footing with college-trained pros was over,” Professional Football Researchers Association (PFRA) members Bob Braunwart and Bob Carroll wrote in 1979. “Many sandlotters still played useful roles with good pro teams, but the key men had earned varsity letters at colleges.”

College graduates, however, were not flocking to the new league, and many saw it as a step down from college football.

Harold “Red” Grange, a superstar at the University of Illinois, elevated the NFL’s prestige and popularity — and negotiated a healthy cut of the profit — when he signed up for a wildly popular barnstorming tour with the Chicago Bears in 1925. (AP Photo)

The NFL’s 1925 signing of Harold “Red” Grange, a University of Illinois star famous for his long touchdown runs, marked a turning point in that thinking. Grange knew the league wanted him as a gate attraction, so he retained an agent — theater owner C.C. Pyle — and negotiated a deal with the Chicago Bears late in the 1925 season for 50 percent of the receipts on an 18-day, 10-game barnstorming tour.

Exhausted and injured, Grange barely completed the tour, but he and Pyle reportedly made $150,000, and the team toured again from late December through January in Florida and California. A severe knee injury in 1927 reduced Grange’s impact as a player, especially on offense, but his impact on the pro game’s prestige and popularity remained.

In 1926, the NFL’S Duluth Eskimos signed Ernie Nevers, a Stanford University All-American and 1925 Rose Bowl hero. In 1927, the league’s Cleveland Bulldogs signed Benny Friedman, a University of Michigan star considered the greatest passer of his day. Both would become headliners for the league, receiving top billing over the team’s they played for.

But signings like those of Grange, Nevers and Friedman were notable in that they remained a relative rarity. The NFL was not attracting and retaining the country’s top talent. In its early days, the league was regional and unstable, with a steady churn of teams and low pay.

Even in 1930, some standouts preferred to play with independent teams in the towns in which they worked rather than moving to join the NFL. And many college players eschewed pro play altogether, using their educations to move into higher-paying professions.

In 1936, the first NFL draft began to formalize the path from college to the pros. By one count, only 24 of the 81 drafted players signed contracts with the NFL — a reflection of the league’s inferior status and low pay levels.

The number one pick in that draft, Jay Berwanger, turned down $125-$150 per game and never even received a response to his request for $25,000 over two years. He took a job as a foam rubber salesman instead.

University of Chicago star Jay Berwanger won the first Heisman Trophy and was the first overall pick in the 1936 draft, but he chose a job selling foam rubber over playing in the NFL; he would later launch a successful manufacturing business. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

The first draft was only partially successful, but it established a method for bringing college players into the game and one for distributing talent fairly among teams. That would become invaluable as the league matured.

The NFL matured significantly during the 1930s and ‘40s. It further distinguished itself from the college game by adopting its own set of rules — many of which boosted the offense — and improving the quality of play on the field.

As the league improved, so did its level of talent. The path to the NFL became clearer as independent pro clubs disappeared. Other leagues would challenge the NFL — the American Football League (AFL) in the 1960s by far the most successful and influential. But the AFL merged with the NFL, as did the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) in 1950, and the others faded away. The NFL became the premier place to play.

The years during and immediately after World War II brought two big player-related developments. One expanded the talent pool; the other changed the type of talent that teams would seek.

African American players returned to the NFL. While several had played in the league’s early days, the league effectively banned African Americans from 1933 to 1945.

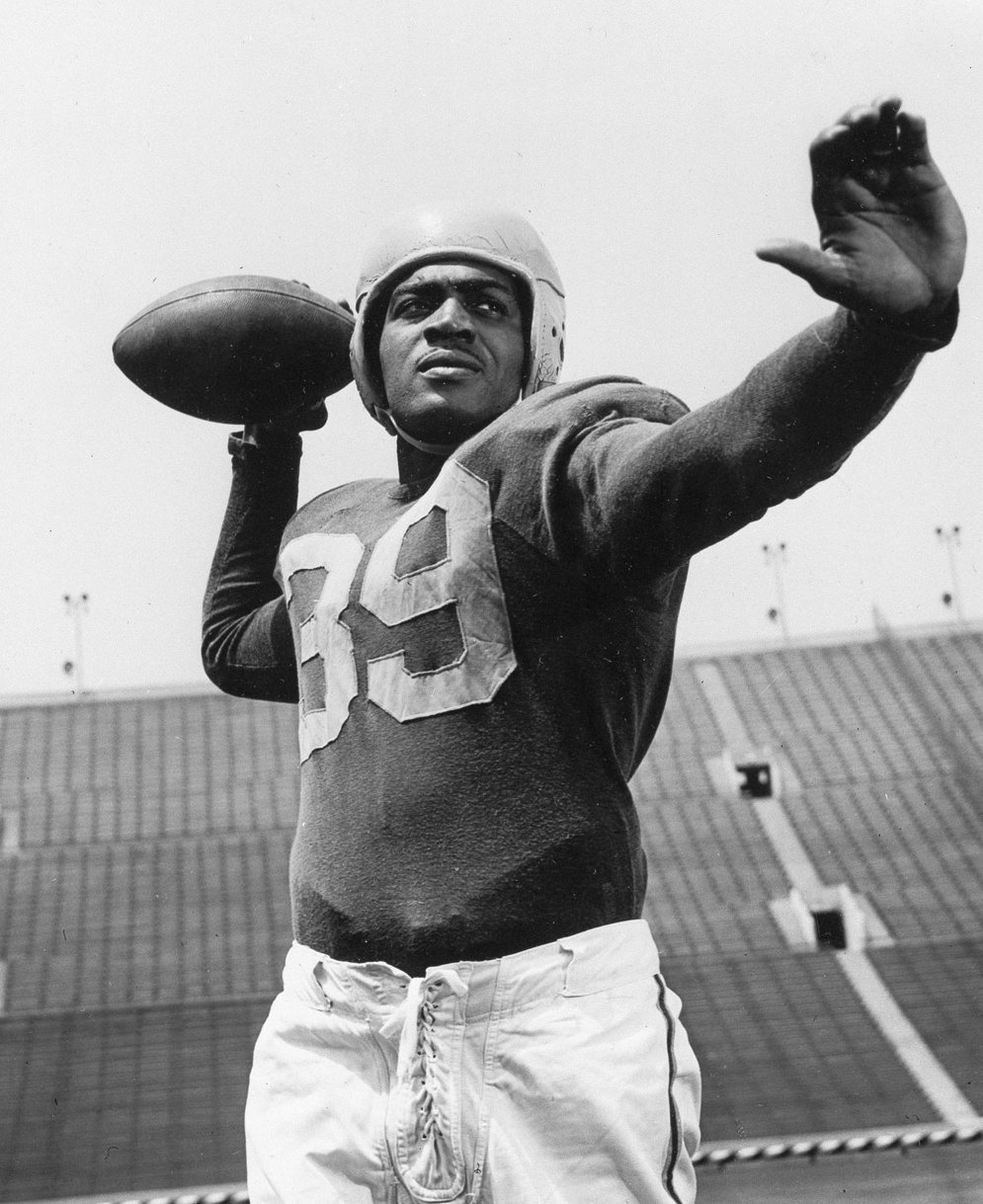

That finally ended in 1946 — a year before Jackie Robinson broke pro baseball’s color barrier — with the Los Angeles Rams’ signing of Kenny Washington and Woody Strode.

That same year, Paul Brown, coach and part-owner of its Cleveland franchise in the upstart AAFC, signed African American standouts Bill Willis and Marion Motley.

Leading up to its 1950 merger with the NFL, the AAFC would actually integrate faster than the NFL.

The other big change involved a rule.

Kenny Washington of the Los Angeles Rams, seen on Sept. 3, 1946. (AP Photo)

In the 1920s though the early 1940s, most players were similar in size because substitutions were mostly prohibited. Players were largely interchangeable and played every play — often playing multiple positions — on offense and defense. Even kickers played every down at other positions.

With America’s young men serving in World War II, the NFL faced player shortages and financial struggles. But the league’s response would forever change the game and the make up of the men who play it.

The shortage of fit players forced the NFL to change its rules to allow free substitutions. The league tried to re-implement its restrictions after the war, but substitutions proved so popular that it lifted its restrictions permanently in 1949.

Players no longer needed to be able to play both offense and defense and could even take the field for just a handful of plays per game. That meant that, for example, coaches could use small and speedy receivers to energize their offenses, since those players would not need the size required to play defense.

Garo Yepremian's Botched Field Goal

Punters and kickers no longer had to block, tackle, run, catch or pass. A club could keep a player primarily to return punts and kickoffs.

Over time, teams’ roster sizes grew, abetting the trend. Teams went from 16 “active list” players available for play in every game in 1925 to 30 by 1938, and 40 by 1964. Since the 2011 season, each team can identify 46 active and seven inactive players before each game. More roster spots meant coaches could afford to reserve spots for specialists.

Specialization was gradual as coaches adopted new strategies to take advantage of players with unique physical attributes and skills — all in the name of trying to gain an edge on their opponents.

Increasingly, kickers became more one-dimensional. Witness Miami Dolphin Garo Yepremian — 5 feet 8 inches and 175 pounds — when he tried to salvage a botched field goal attempt in his team’s 14-7 Super Bowl VI victory over the Washington Commanders That play was not his finest moment, but his kicking prowess made him worthy of a roster spot — Yepremian was named to the NFL All-Decade for the 1970s. Like any specialist, kickers needed to excel only at the job they were hired to do.

Cleveland Browns guard Chuck Noll (a future Hall of Famer for his coaching triumphs with Pittsburgh) was a salesman for Trojan Freight Lines in the offseason. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

The late 1950s saw an explosion in football’s popularity, particularly after the 1958 Championship Game between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants, which is still considered by some as “the greatest game ever played.” Player pay, however, was slow to catch up.

A Cleveland Plain Dealer story told the story of how almost all Browns players worked second jobs in the early 1960s during the six-month off-season to supplement their income.

Future Hall of Fame defensive end Willie Davis taught students mechanical drawing in 1961. Linebacker Jim Houston, a first-round pick in the 1960 draft, opened an insurance and financial planning company. Guard Chuck Noll (future Hall of Famer for his coaching triumphs with Pittsburgh) was a salesman for Trojan Freight Lines.

Off-season conditioning was not the norm, because players spent it working and pursuing other interests.

By the early 1970s, football had overtaken baseball as the country’s favorite spectator sport. Television contracts, sold-out stadiums, merchandising and sponsorship deals ensured an abundant, steady flow of cash.

In the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the growth of the NFL Players Association — first formed in 1956 with Cleveland players as a nucleus — gave players more say in how their profession developed and contributed to a big boost in salaries. So, too, did the ever-rising profitability and popularity of the game.

Today’s NFL players spend off seasons in rigorous conditioning, exercise and nutritional programs preparing for the next season. Clubs work with the players to provide sophisticated training techniques, equipment and medical expertise year-round.

Future NFL stars now start with youth football and play through high school and college, all with support systems in place to develop players at every level. Top athletes may make it to the NFL, and most players are often more fit and prepared for the professional game than ever before.

Players have grown in many ways over the past three decades — in professionalism, earnings, specialization, size and strength.

High school quarterbacks learn to read defenses, and defenses use line stunts and blitz packages. Specialization takes hold early. Many major college programs have adopted pro-style offensive schemes creating players more prepared to adjust to the NFL game.

Increased specialization in the NFL and the evolution of offensive and defensive coaching strategies have led to new optimal body types for each position, with customized conditioning and nutritional programs to match.

NFL Players at most positions are bigger and stronger than their predecessors, but sizes and body styles have diverged — sometimes dramatically — based on the demands of their roles. As data journalist Noah Veltman noted after crunching the numbers on NFL player height and weight over time, “nowadays, if you’re 6 foot 3 inches and 280 pounds, you’re too big for most skill positions and too small to play line.”

One recent analysis of average player weights by position, using data from NFL.com for each player on 2013 rosters, found a range from 193 pounds for cornerbacks to 315 for offensive guards. (The difference in average heights, while not as dramatic, ranged from 5 foot 11 inches for running backs and cornerbacks to 6 foot 5 inches for offensive tackles.

Nowhere is the divergence more evident than on the offensive and defensive lines.

In the early 1980s, Washington line coach Joe Bugel told Joe Jacoby, a 6 foot 7 inch, 275-pound offensive tackle at the University of Louisville, that he had a chance to make it in the NFL — but only if he got bigger.

Washington Commanders offensive tackle Joe Jacoby was a giant among men, but he actually had to bulk up to make it in the NFL. (AP Photo/Al Messerschmidt)

With training, Jacoby increased his bench press from 300 to 400 pounds, put on 30 pounds and increased his quickness in the 40-yard dash to five seconds flat. He made the team as an undrafted free agent in 1981 and became part of one of the most famous and dominant offensive lines in NFL history — the “Hogs” — which powered the team to three Super Bowl titles.

But in terms of size, the “Hogs” wouldn’t look that imposing today. Even Jacoby — so imposing that one writer said of him, “Andre the Giant wears his hand-me-downs” — wouldn’t stand out. By 2013, the median weight for NFL guards and tackles had reached 310 pounds, according to one analysis. That means over half weigh more than Jacoby did.

One of the smallest Hogs — Hall of Famer Russ Grimm — stood 6 feet 3 inches and weighed 273 pounds. Today, he would be one of the league’s smallest guards.

For defensive ends, the need for speed and agility to rush the quarterback may mitigate some of the size increase. Ends averaged 283 pounds and 6 feet 4 inches tall, the analysis of 2013 NFL rosters found.

But defensive tackles, responsible for shutting down an opponents running game, averaged 6 foot 3 and 310 pounds. Compare that to NFL legends like Mean Joe Greene, the 6 foot 4, 275-pound tackle for the Pittsburgh Steelers from 1969-81, or Dallas Cowboy Hall-of-Famer Randy White, who played the position for the Dallas Cowboys from 1975-1988 at 6 feet 4 inches, and 257 pounds.

The impression that players at every position are much bigger and stronger than previous generations is not always true. Sometimes the ideal body type for today’s game is actually smaller. Consider the running back.

Bronko Nagurski, the ball carrier who became the NFL’s symbol of power football during the 1930s, stood 6 feet 2 inches tall and weighed 226 pounds. His strength and size helped him plow through would-be tacklers.

Running backs today average just shorter than 6 feet, and 215 pounds. On those terms alone, Nagurski would not be outmatched. But today’s runners use their size to hide behind the massive linemen blocking in front of them, and spend countless hours in training to develop the acceleration and lower body strength to speed through holes and fight for extra yardage.

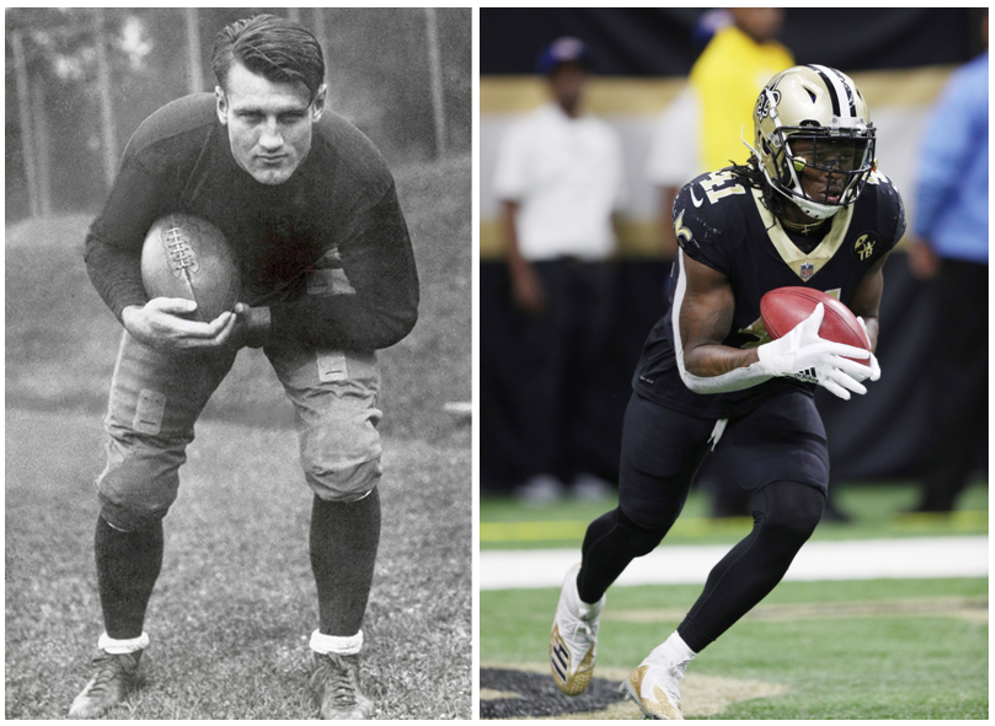

At 6 feet 2 inches and 226 pounds, 1930s Hall of Fame running back Bronko Nagurski was bigger and heavier than many of today’s stars, like New Orleans’ Alvin Kamara (5-10, 215), but he likely did not share some of their specialized skills, strengths and abilities. (Pro Football Hall of Fame) (Margaret Bowles via AP)

Quarterbacks do not necessarily stand taller either. Stars from different generations of play — Sammy Baugh (6 feet 2 inches), Bart Starr (6 feet 1 inch) and Joe Montana (6 feet 2 inches) — would not have to look up at most of today’s stars.

But like the majority of today’s players, body mass is greater — perhaps a beneficiary of training and a reflection of the need to withstand hits from those bigger defensive linemen. The average weight has risen to about 224 — more than 20 pounds above the playing weights of Baugh, Starr and Montana.

But beyond size, players are different today because of their football environment.

Their support system through youth leagues, high schools and college — from the leagues and schools themselves and NFL-sponsored events and player development programs — is unprecedented. Relieved of the need to play on both sides of the ball on every down, they have honed their skills at specific positions. Given the time and resources, they have maximized their fitness and become greater students of the game.

Professionals now in every sense of the word, they are the best of the best, a specialized elite, continuing to elevate the game.