Officiating crews from professional football's earliest days wouldn't be recognizable to today's fans — and not just because of their attire (white dress shirts, black bow ties) and their use of horns, rather than flags, to call penalties.

The level of professionalism would be just as unfamiliar. Undertrained, ill-equipped and loosely supervised, the officials contributed to the sluggish, low-scoring, rough-and-tumble games the NFL produced in its infancy.

For professional football to grow and improve, the quality of officiating needed to get dramatically better. New rules designed to make the game fairer, safer and more entertaining would be of no use without officials who could properly and consistently enforce them.

Fortunately for the game and its fans, the league found visionary and demanding leaders who helped officiating evolve from those humble beginnings to the highly trained, rigorously evaluated and technologically savvy stewards of the game we know today. That process began in earnest in the late 1930s.

The First Steps Toward Excellence

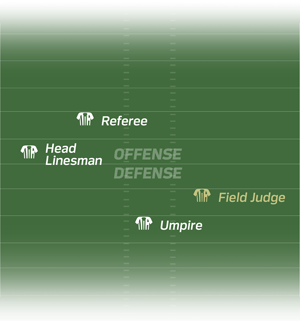

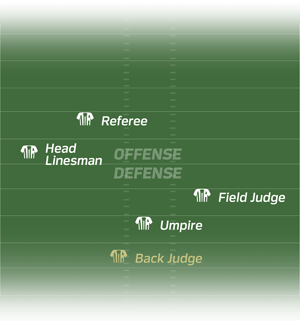

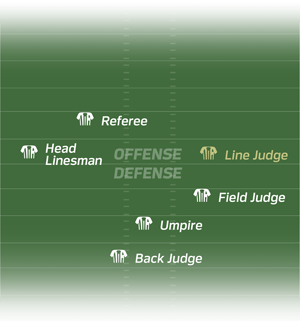

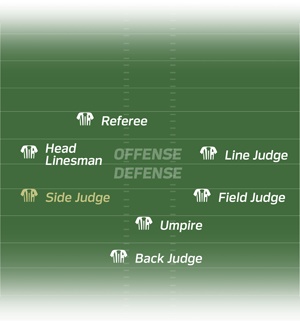

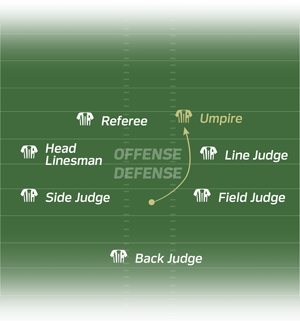

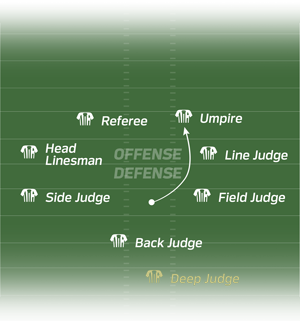

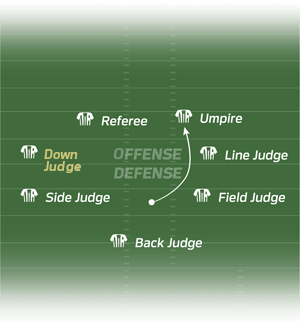

The year 1938 would be a turning point for NFL officiating for two reasons: Officials were assigned to dedicated positions on officiating crews, and the league hired a man who would forever change the game.

Until that year, an official may have worked at a different position on a crew from week to week. In 1938, the league instituted a new system in which each member of the four-man unit was permanently assigned to one specific position.

This established consistency from game to game and created specialists at each position on the field. In the ensuing decades, the crew continued to evolve as the league added three more positions to keep up with changes in the game (and it's currently considering adding one more as the speed of the game continues to increase).

The NFL's officiating crews have grown along with the game. See how the league got to today's seven-person crew, with the addition of an eighth official under consideration.

‘Shorty' Raises the Bar and Changes the Game

The second turning point occurred when the league hired Hugh "Shorty" Ray, a 5-foot-6, 136-pound innovator who became a titan of the game.

Before he joined the NFL, Ray was working with a national high school football association to develop a rulebook specific to high school football. The Highland Park, Ill., native — who had decades of experience as a three-sport official — already had helped to transform officiating in the Chicago area with the Chicago Schools Athletic Officials Association.

Conscious of the shortcomings of the state of officiating crews and brimming with ideas for improvement, Ray rewrote the nation's high school football rules. He organized clinics across the country to teach his rulebook and officiating system and demanded that his officials pass rigorous rules exams.

Ray also is credited with introducing an officiating "play situation book" to the NFL — a guide to prepare officials for every possible scenario during a football game. The league continues to use a situation book today.

Ray was rethinking how the game was governed, officiated and played, and George Halas, the legendary owner and coach of the Chicago Bears, took notice. Halas recommended that the league hire Ray as a technical adviser in 1938. The game — and officiating — would never be the same.

"Getting the league to hire ‘Shorty' Ray was my finest contribution to pro football."

George Halas, Hall of Fame coach

Chicago Bears owner/head coach George Halas (left) and NFL Commissioner Bert Bell (right) shake hands with Hugh "Shorty" Ray in the 1950s.

Ray served as a technical adviser from 1938 to 1952, a period in which the NFL reached new heights of popularity. He routinely met with officials to improve their technique and demanded that they be experts on the rulebook. He also visited every team's training camp to teach coaches and players about the streamlined rulebook and new points of emphasis, all with the goal of making football safer, faster and better.

Today's Officiating Department takes similar steps to ensure that every official is an expert on the rulebook.

"He pounded the rules into his officials so that they could average 95 percent of a test at a coaching clinic on even the most difficult problems. Before that, they couldn't reach that score — even with the book open at their elbow."

Mark Duncan, NFL Supervisor of Officials, 1964–1968

In 1966, 10 years after his death, Ray became the first — and so far only — officiating figure to be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

"Of course," Ray said, "I've had very little to do with all this. Football is not one man's game."

Tough Love and Technology Raise the Bar

Ray's devotion to the game, demand for professionalism and innovative thinking elevated officiating to the level needed to improve the credibility of the NFL product. Nonetheless, more work would be needed to raise officiating to the level it has reached today.

Mark Duncan, a former San Francisco 49ers coach and future Seattle Seahawks assistant general manager, oversaw the Officiating Department from 1964 to 1968. He required officials to take yearly tests and attend preseason clinics, but it wasn't until Art McNally assumed the head position that the level of officiating would truly blossom.

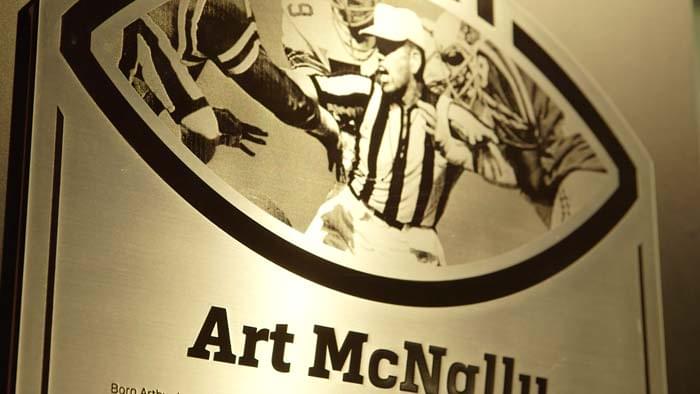

In 1968, McNally was named NFL supervisor of officials, a position he held until 1991. A longtime official from Philadelphia, he would become one of the key people in the Officiating Department's transformation.

During McNally's time with the league, his name became synonymous with officiating excellence. Under his leadership, the NFL's Officiating Department developed its modern evaluation and grading system for officials — a critical component in improving proficiency and boosting the game's integrity. He introduced the idea of weekly performance reviews and held his officials to strict standards.

When asked if an official in the right position on the field will make the right call nine out of 10 times, McNally responded: "Higher than nine times out of 10. It better be, or he'll be out of the business. He won't be around for long."

McNally, a former Marine, showed his officials tough love but was confident in their ability to do their job the right way. "Overall, the caliber of our officiating is excellent," he told the Philadelphia Daily News in 1990. "I grade the films, eight hours a day, so I should know."

The rigid, innovative and effective weekly evaluation system under McNally was as follows:

-

Step 1

McNally and his aides reviewed the game film and noted every foul that was called and the official who called it.

-

Step 2

The team graded each foul call on a seven-point scale, from poor (1) to excellent (7).

-

Step 3

McNally then looked for any plays in which a foul should have been called but no whistle was blown.

-

Step 4

In addition to each call or no-call, the team graded each official on mechanics and positioning.

McNally's wasn't the only evaluation; the referee, an NFL observer (watching from the stadium press box) and each team's coach also submitted numerical grades to the Officiating Department. Once all the grades were filed, McNally condensed them into a single cohesive report — ready to send to the officiating crews each week.

McNally and his team were simply using a blank, white wall on which to project their film. But he envisioned something grander: a centralized officiating headquarters with even greater capabilities. His command center vision became a reality in the early 1990s.

McNally also recognized the importance of creating specialists at all seven officiating positions. He organized meetings by position to provide a chance for every crew member to discuss his specific challenges and solutions.

"Because of Art's honesty, integrity, vast experience and dedication, no coach disregards what he has to say."

Hall of Fame coach Don Shula

Technology — and the league's use of it — also caused an evolution in officiating.

Referees were equipped with wireless microphones in 1975. The microphones allowed officials to explain on-field rulings to a much wider audience, and fans watching on television — along with those in the stands — got a sense of the officials' personalities for the first time.

Colorful referees like Mason "Red" Cashion and Jerry Markbreit experienced unprecedented levels of fame and recognition. Anonymity had been viewed as a sign that the officials were doing something right, but now, every Sunday, Cashion's famous "First down!" call was heard in living rooms across America.

Beyond the entertainment value, the ability for fans to hear the calls added credibility to on-field rulings, increased transparency on rulings for fans and the media, and reinforced the integrity of the game.

Instant replay would do that too.

The league first experimented with instant replay in 1976. McNally, curious to determine how long a video review would delay a game, watched a "Monday Night Football" contest between the Dallas Cowboys and the Buffalo Bills with a stopwatch and a video camera. He saw a missed call involving O.J. Simpson that could have been corrected with replay review. Two years later, the league tested instant replay as an officiating aid during seven nationally televised preseason games.

It would take many years before instant replay would become an NFL fixture: adopted for the regular season in 1986, rescinded in 1992, then brought back for good in 1999. But McNally helped it take root.

After serving in the NFL's Officiating Department for more than 20 years, McNally retired in 1991. His tenure modernized the evaluation and craft of officiating and led to an increase in football's popularity across the United States.

"This has been a tough job," McNally told The New York Times before his final season, "but I think we've accomplished a lot for the league."

Officiating for the Modern Age

In 1991 the NFL passed the officiating torch to 16-year veteran Jerry Seeman. Having earned the honor of refereeing the Super Bowl twice, Seeman was already highly respected in the Officiating Department before his promotion.

Shortly after the league appointed Seeman supervisor of officials, one of his predecessor's dreams — an officiating command center — became a reality. This centralized hub was a first in American sports and supported what many considered the most exhaustive officiating evaluation system of its time.

The early '90s command center included $500,000 worth of cutting-edge technology. Streamlined video review was now possible, and Seeman and his crew improved the department's evaluation process.

In a 1993 article in Referee magazine, Jack Reader, assistant director of officiating under Seeman, compared the new and old systems: "We would sit there splicing plays together by hand using a razor blade and adhesive tape. Now [we do] it all by computer, using digital sequencing and numerical coding to signify exactly where, on any given tape, a particular play is located."

While the improved technology certainly altered how the Officiating Department was run, Seeman continued to stress the human aspect of officiating. As he said in 1993: "Computers make it possible, but people make it happen."

Even as the Officiating Department continued to improve its evaluation system and technological aids, Seeman saw the need for his crews to get more physically fit. No formal conditioning program existed, and officials were weighed only twice a year. Seeman added a physical exam and a stress test, with the results analyzed by a cardiologist. He also demanded long-distance runs, sprints and individual weight goals for each official.

"Jerry just wants to make sure everyone's in shape," head linesman Mark Baltz said in 1991. "As a longtime referee, he knows the importance of conditioning."

In addition to the new emphasis on physical fitness, Seeman updated a tool that Ray had introduced to the NFL some 60 years earlier: He edited an 85-page officiating casebook, filled with specific play examples, for his officials to study. Decades after Ray's enshrinement in the Hall of Fame, his influence was still felt.

In 1999 Seeman oversaw the return of instant replay, which had been rescinded seven years earlier because owners felt it slowed down the game too much without getting enough calls right. The new version featured more advanced technology and a more efficient system for initiating and completing reviews. Still, Seeman emphasized that instant replay should be considered just one of the tools in the officiating toolkit to assist his crews in their pursuit of excellence.

"People have to understand what the purpose of replay is: It's a tool to help out officials in very isolated cases," Seeman told the Los Angeles Times in 1999. "We would love to get every call right, but that isn't always the case."

After a three-year bout with cancer, Seeman died in November 2013 at age 77. To recognize his commitment and achievements in officiating, every official wore a patch with Seeman's initials on their gameday hat for the remainder of the 2013 season through Super Bowl XLIII.

Continuing the Quest

The NFL’s instant replay system took another big leap forward in 2014, when the league opened Art McNally GameDay Central (AMGC) — the officiating command center at league headquarters in New York, where an inscription outside the center’s doors pays homage to the man who led the department for more than 20 years.

Dean Blandino, the league’s head of officiating from 2013-2017, led the NFL department as it transitioned into a new technological era. Blandino’s experience as an instant replay official from 1999-2003 and the NFL’s top replay manager from 2004-2009 prepared him to use AMGC’s 89 monitors, 16 replay stations and proprietary NFL Vision software on every challenged or reviewed call to make sure it was resolved efficiently, accurately and consistently.

In 2014, the league began consulting directly with the referee and the game’s replay official during reviews from inside AMGC. A senior officiating department representative would confer on the play in question, with the referee making the final call.

The league debuted a more efficient wireless official-to-official communications system (O2O) for the same season. The system speeds up the game by letting the officiating crew talk to each other from a distance instead of face-to-face for every penalty. For example, O2O saves time when a field judge flags a clear pass interference 45 yards downfield and can tell the referee about the call as soon as the play ends.

Beginning with the 2017 season, the league continues to consult with the game’s referee and replay official from the AMGC, but now, final decisions on all replay reviews come from a designated senior member of the officiating department with input from the referee. The centralized decision-making is another step the league has taken to reinforce consistency in how the final calls are made, no matter where or when the game is played.

Still, some things will stay the same. For those who pursue football officiating perfection while performing under a microscope, McNally put it best: "One thing hasn't changed: the pressure. It will always be there."