History of Instant Replay

Upon further review…

Upon further review…

The NFL has come to embrace instant replay, but the process that led to the state-of-the-art system the league uses today was not always seamless. The history of instant replay in professional football is filled with stops and starts; missteps and controversy; and modifications and improvements that continue to this day.

Instant replay’s history begins in earnest four decades ago — with a man and a stopwatch.

The NFL first experimented with instant replay in 1976 when Art McNally, then the director of officiating, wanted to find out how long a video review would delay a game. Equipped with a stopwatch and video camera, he observed a "Monday Night Football" contest between the Dallas Cowboys and Buffalo Bills from a press box inside the stadium.

“If there was any question, we took a look at it,” McNally said after the experiment. “We asked the camera technicians to give us different angles.”

He saw a missed call on a play involving O.J. Simpson that could have been corrected with replay review. McNally knew then: Replay could help football.

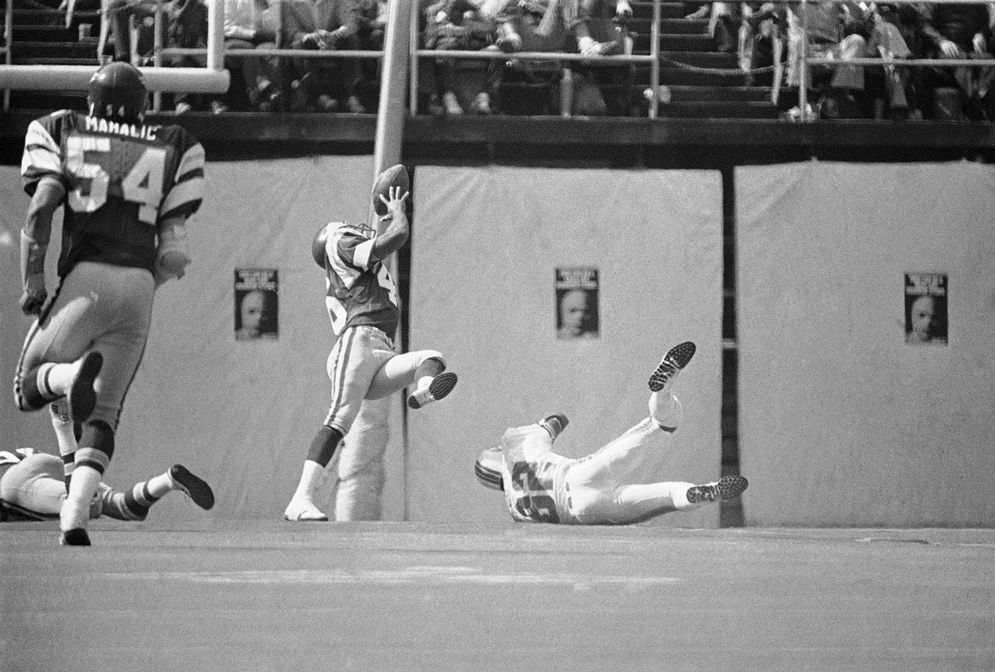

The NFL tested instant replay during the 1978 Hall of Fame game and six other preseason games that year. It determined the system was not yet ready for regular-season games. (AP Photo/Rusty Kennedy)

Two years later, the league first tested instant replay on a wider scale during seven nationally televised preseason games, starting with the 1978 Hall of Fame game between the Philadelphia Eagles and Miami Dolphins.

The system’s performance was lackluster. The technology was too costly to install at every stadium, the system needed more cameras than broadcasters used for games at the time, and calls remained inconclusive after lengthy reviews. It was clear instant replay was years away from being implemented full time.

“We still think we need a minimum of 12 cameras to get all the angles on every play,” then-assistant supervisor of officials Nick Skorich said after that first game. “Electronically, I don’t know if we are advanced enough yet.”

Unwilling to implement a costly and ineffective system, the league shelved instant replay until the mid-1980s.

Less than a decade after McNally’s experiment, momentum for an instant replay system once again began to build.

The NFL tested a review system during eight preseason games in 1985 — producing promising results.

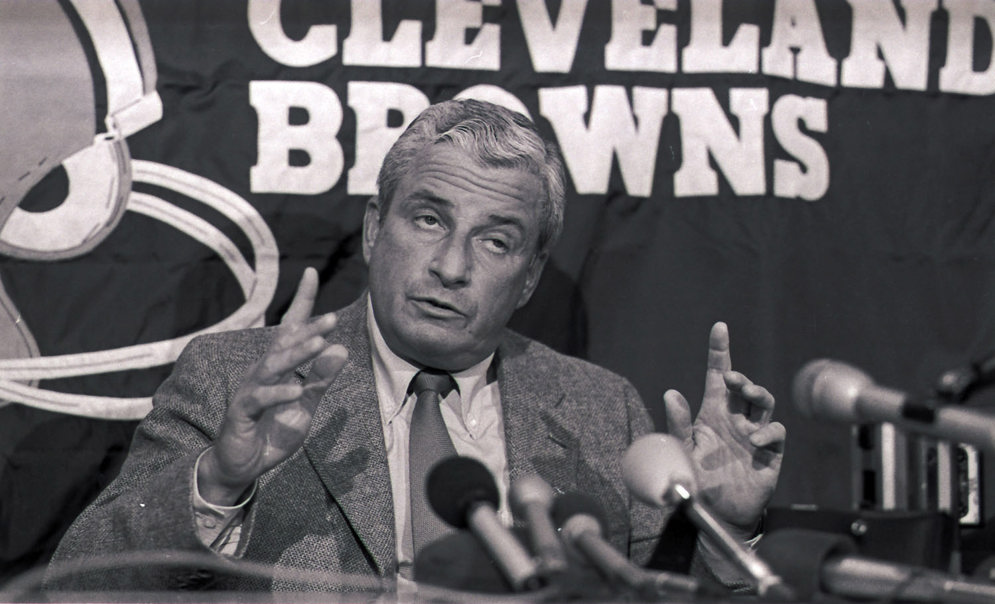

Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell delivers a message during a 1982 news conference. (AP Photo/Mark Duncan)

“The thing we learned in the preseason is that we can get the logistical things done,” NFL Director of Administration Joe Rhein said. “That is, it’s possible to review instant replays [in the press box] and get the word to the referee on the field without a significant loss of time.”

The system performed so well that owners held an unprecedented vote to determine if the league would use instant replay in the upcoming playoffs — even though the system had never been used in the regular season. The motion failed narrowly, but the close decision made it clear the league’s leaders were once again warming up to the technology.

“[Owners] didn’t want a playoff game decided by a bad call, and so they tried to push it through right there,” Art Modell, Cleveland Browns owner, said after the vote. “But that was a little too quick for some people.”

“Some clubs may have voted against it at the time because it was adding something for the postseason that was not available during the regular season,” NFL spokesman Joe Browne said at the time.

In the proposed 1985 system, a replay official would have monitored the game feed from an in-stadium booth and initiated all reviews, reversing a call only with “indisputable visual evidence.”

Prior to the 1986 season, the owners voted 23-4-1 — 21 votes were needed to pass — to adopt limited use of instant replay in the upcoming year. The initial process lacked the coach’s challenges and technology familiar to today’s fans. Most reviews were initiated upstairs by the replay official, except when game officials requested a review of their ruling after conferring on the field.

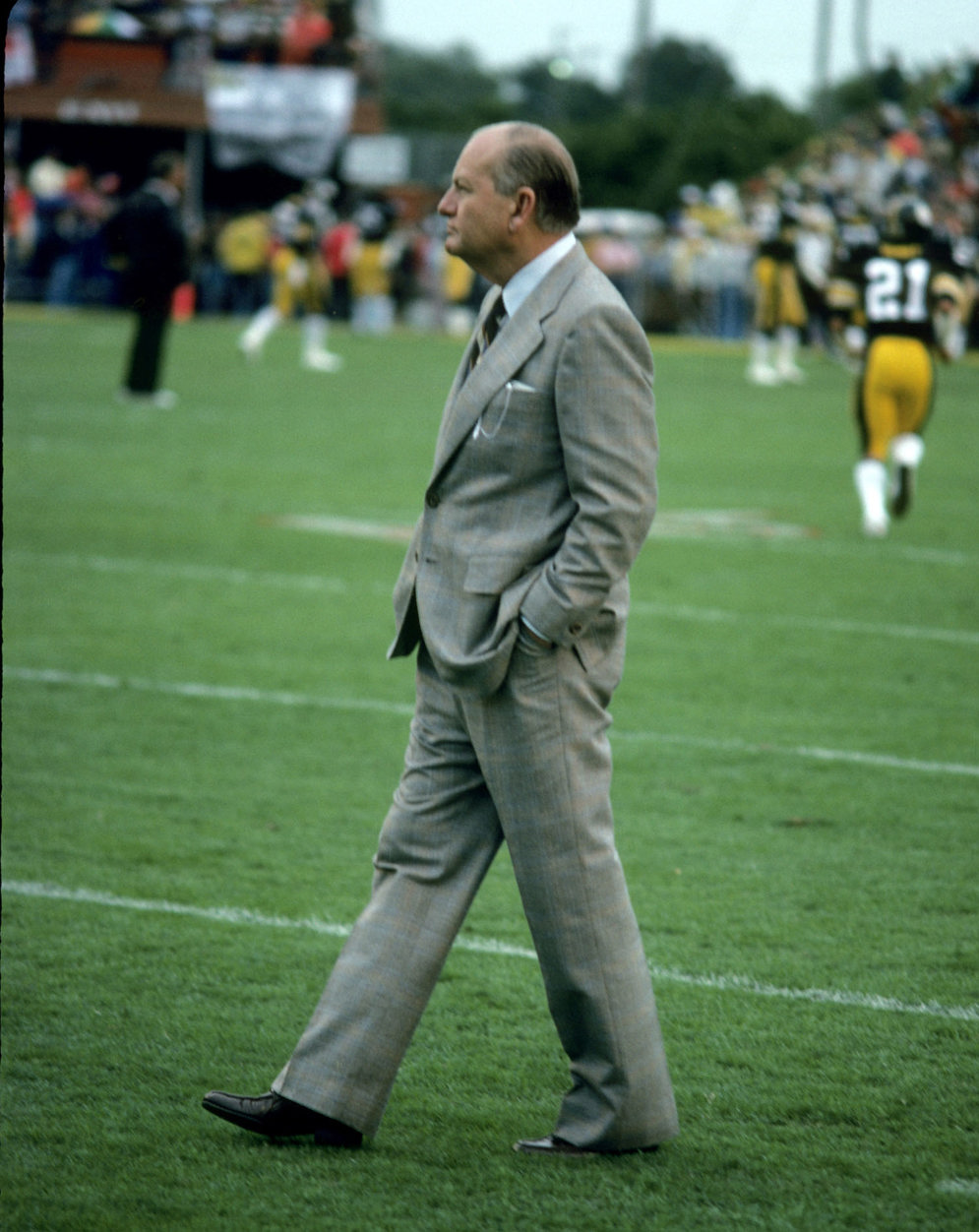

Dallas Cowboys president and general manager Tex Schramm stalks the sidelines before Super Bowl XIII, a 35-31 loss to the Pittsburgh Steelers on Jan. 21, 1979. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

Reviewable plays during instant replay’s first installation included:

The decision was only reached after a spirited debate and concessions to appease skeptics. The compromise: The system would be guaranteed for only one year and would have to be voted on again during the following offseason.

“Some feel we are taking the human element out of the game and moving it to a booth in the press box,” said Tex Schramm, who then served as Dallas Cowboys general manager and NFL Competition Committee chairman.

Replay officials sat in a booth in the stadium with two nine-inch television monitors showing the broadcast feed and two videocassette recorders. The two VCRs were capable of recording and immediately replaying individual plays. Reviews would be a maximum of two minutes, timed from the moment when the umpire signaled timeout.

First use of instant replay in 1986 Week 1 between the Browns and Bears.

Instant replay’s first regular season saw an average of 1.6 reviews per game. Of those plays in question — 374 in all — only 10 percent ended with a reversal of the ruling on the field.

The owners reapproved instant replay for the next season. Barely. The measure got exactly the 21 votes needed to pass (21-7) and was accepted with a few minor tweaks. But just like the 1986 decision, the system would have to be approved again the following offseason.

Some adjustments were made in an attempt to improve the system. To ensure replay officials were experts on the technology, the NFL would now hold a training clinic each offseason. The equipment improved as well, albeit slightly, as review monitors were upgraded — from nine inches to 12 inches.

“I’m confident the system will get better and better,” Hall of Fame Miami Dolphins coach Don Shula said after the ’87 vote. “As coaches, we realized we can’t see a game from the sidelines as well as our coaches can from upstairs in the press box. If you transmit that same thinking to officials, it helps them too.”

The first system did not lack controversies — or critics.

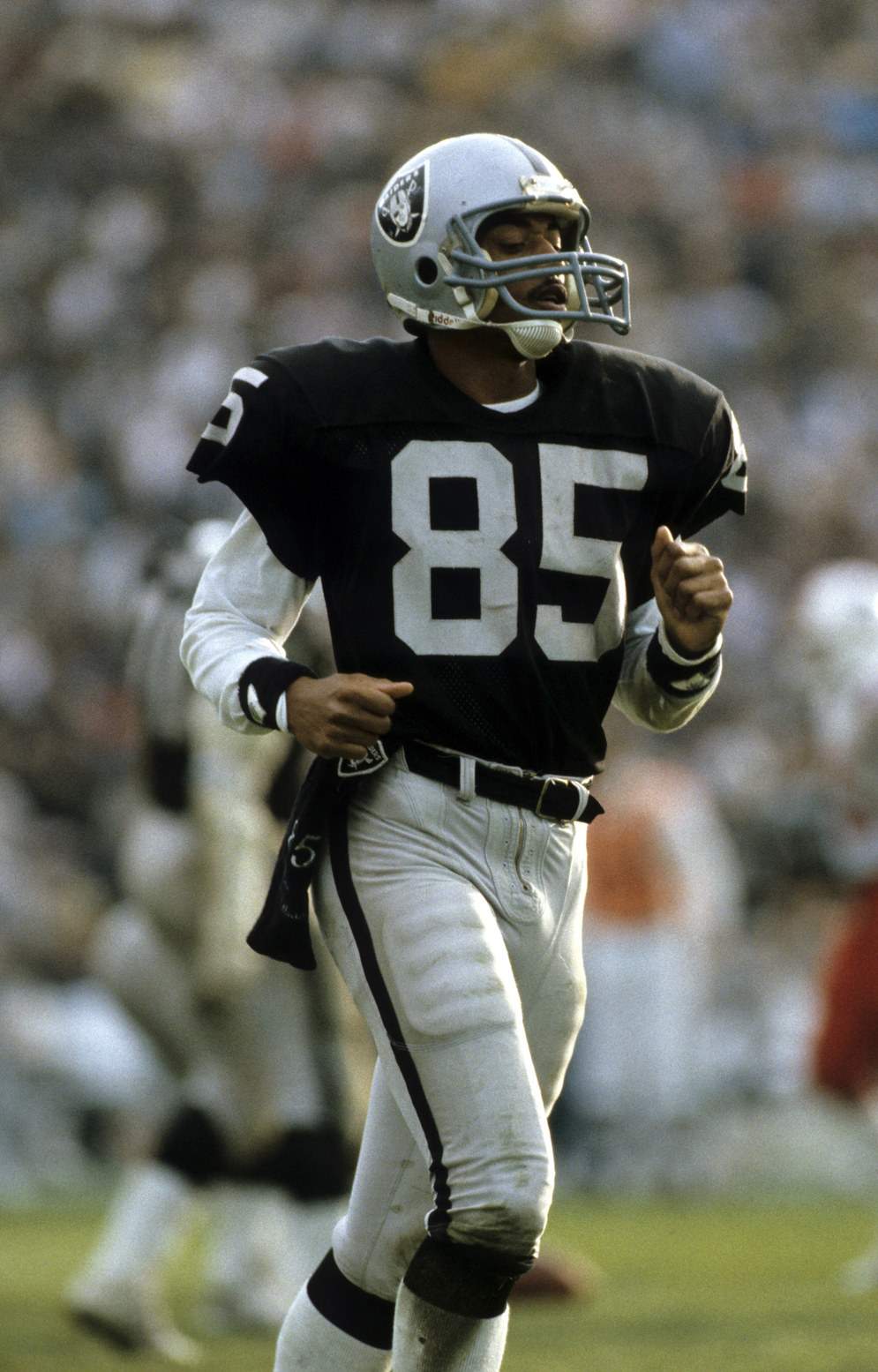

A miscommunicated instant replay call in October 1986 awarded Oakland Raiders receiver Dokie Williams a touchdown on a play that should have been ruled an incomplete pass. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

During a Kansas City Chiefs and Oakland Raiders game in October 1986, Raiders quarterback Marc Wilson threw a pass to Dokie Williams in the corner of the end zone late in the first half. The on-field officials ruled the play a touchdown. But up in the instant replay booth Jack Reader, assistant supervisor of officials, determined it was incomplete.

“Pass incomplete,” Reader told umpire John Keck with the walkie-talkies used for instant replay system communication.

“Pass is complete,” Keck heard. Inadvertently, the touchdown stood. The Raiders won by a touchdown — 24-17.

“My buddy, the instant replay guy,” Williams jokingly said after the game.

But the miscommunication was no laughing matter to the NFL. The league replaced its walkie-talkies with pagers and radio headsets and it changed the terminology, using clearer terms like “confirmed” and “reversed.”

NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue, long a proponent of instant replay, was eager to improve the system.

“I’m hopeful we can make some modifications and keep the concept and make it work rather than step back out of the electronic age,” he said in 1990.

The commissioner’s hopes were dashed. After a six-season run, instant replay met its demise in 1991 when 17 owners voted against renewing the system. The belief: The system delayed games too much and failed to get enough of the calls correct.

|

Year |

Games |

Plays Reviewed |

Reversals |

|

1986 |

224 |

374 (1.6 per game) |

38 (10%) |

|

1987 |

210 |

490 (2.3 per game) |

57 (11.6%) |

|

1988 |

224 |

537 (2.3 per game) |

53 (9.8%) |

|

1989 |

224 |

492 (2.1 per game) |

65 (13%) |

|

1990 |

224 |

504 (2.2 per game) |

73 (14.4%) |

|

1991 |

224 |

570 (2.5 per game) |

90 (15.7%) |

|

1986–1991 |

1,330 |

2,967 (2.2 per game) |

376 (12.6%) |

“Basically, it was a great theory that didn’t work in practice,” said Norman Braman, owner of the Philadelphia Eagles.

Other owners, like New Orleans Saints President and NFL Competition Committee Chairman Jim Finks, believed the system should have been improved rather than tossed away.

“I personally feel it is a major step backwards,” Finkssaid. “There will be much more pressure on the guy on the field.”

Ultimately, the system’s ineffectiveness led to the end of its use. The league determined that nine of the 90 reviewed calls in 1991 were overturned incorrectly. And only 13 percent of the total plays reviewed from 1986 to 1991 were reversed, fueling critic’s arguments that this was not the right system.

The debate over instant replay, which never completely ended, picked up again in the mid-’90s.

Many of the league’s head coaches at the time did not have firsthand experience with the previous version, so they were curious about how an improved system would work.

“My sense is that everybody feels that if we’re going to have replay, we should look for a concept that works,” Tagliabue said in 1996. “But we want to do it right.”

Referee Bob McElwee reviews a play with an on-field monitor during the 1996 preseason testing of the new system. (AP Photo/Bill Kostroun)

A new system was approved for testing in 10 preseason games in 1996. Coaches could challenge rulings on the field and replay now covered three categories of plays: out of bounds, number of players on the field and scoring plays.

Each coach could challenge three plays per half — at the cost of a timeout per review. The league went away from the old version of replay officials in skyboxes and gave referees the authority to review plays on the field inside a booth equipped with monitors. And referees now had only 90 seconds to make their ruling.

Despite the changes, owners voted against implementation for the 1997 regular season. The main hang-up centered on each review costing teams a timeout, even when a challenge was successful.

Heading into the 1999 season, the Competition Committee again adjusted its proposal to address owners’ and coaches’ concerns. Voters responded, overwhelmingly approving the new system 28-3. Instant replay review was back in the NFL.

The new system addressed some of the main criticisms of past versions.

“I guess [the voters] felt this was a compromise,” Tampa Bay Buccaneers coach Tony Dungy said, “that it won’t slow the game down too much while it still lets coaches coach during the last two minutes of both halves.”

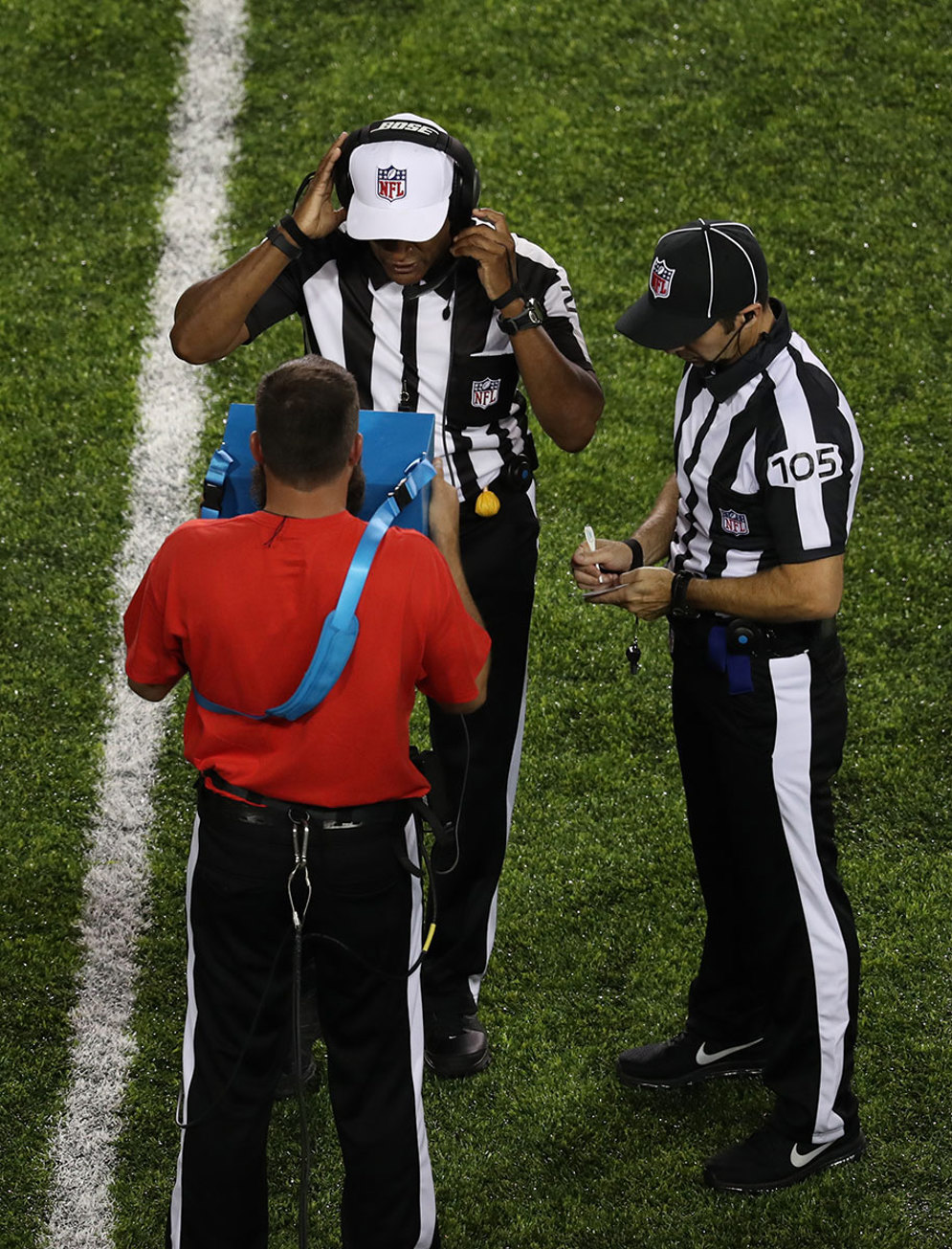

Beginning in 2017, referees started viewing replays on wired, hand-held Microsoft Surface tablets.

Since its return, the league has taken steps to improve the process and limit errors as much as possible — and technology continues to catch up with the ambitious task of replay review.

Long gone were the VCRs and small monitors. Referees now viewed multiple angles at one time using three touch-screen monitors under the hood. Mike Holmgren, co-chairman of the Competition Committee, said: “We’ll get the best technology available.”

Tweaks to replay review continued throughout the decade. In 2004, a reward was added for coaches who were successful on their first two reviews: a third challenge. That same year, owners extended the replay system for the next five seasons — with the hopes of permanently approving the tool in the near future.

“Hopefully, the next time we put it up for a vote we can make it permanent,” Baltimore Ravens general manager and Competition Committee member Ozzie Newsome said after the five-year extension.

Newsome’s wish came true just a few years later. A 2007 decision put an end to what had become a yearly debate. With a 30-2 owner’s vote, instant replay became a permanent fixture in the league.

“It’s a long time coming. Instant replay is an accepted part of the game,” said Atlanta Falcons general manager and Competition Committee Co-Chairman Rich McKay.

The NFL made the switch to high-definition review systems in 2007 — the first of its kind in major American sports. Officials now could review images five times sharper than the previous iteration and freeze images for a closer look. The improved systems were installed in every stadium for $300,000 per team.

“This is a rare opportunity to leverage cutting-edge technology to improve the integrity of the game. Our referees will now be able to see images much more clearly, giving reviews in critical situations the level of scrutiny they truly deserve,” said Mike Pereira, NFL’s vice president of officiating from 2001 to 2009.

In the 2014 season, senior officiating staff members inside Art McNally GameDay Central (AMGC) in the league’s New York headquarters began consulting directly with the referee during reviews. The move helped ensure that calls are being made consistently across the league.

The review process started in New York. As the referee gathered details about the challenge, replay officials in the stadium and in AMGC compiled the best available angles from the broadcast feed. By the time the referee arrived at the booth, the best replays were queued up and ready for review. The change to a consultation model was aimed at reducing the review’s impact on the length of the game.

While the consultation model largely remains in place today, the Competition Committee voted to make two additional changes before the 2017 season. Final decisions on all replay reviews would come from designated senior members of the officiating department in AMGC and referees view all replay video on wired, hand-held Microsoft Surface tablets.

Ahead of the 2021 season, the NFL expanded its replay rule to allow replay officials and designated members of the officiating department to assist on-field officials in specific, limited game situations. This move has dramatically reduced the number of coaches' challenges and AMGC/booth reviews.

| Year | Games | Total Plays Reviewed | Avg. Reviews/ Game | Total Plays Reversed | Percentage of plays reversed | Avg. Delay/ Review |

| 1999 | 248 | 195 | 0.8 | 57 | 29% | 2:54 |

| 2000 | 248 | 247 | 1.0 | 84 | 34% | 3:05 |

| 2001 | 248 | 258 | 1.0 | 89 | 34% | 3:04 |

| 2002 | 256 | 294 | 1.1 | 94 | 32% | 3:01 |

| 2003 | 256 | 255 | 1.0 | 66 | 26% | 3:13 |

| 2004 | 256 | 283 | 1.1 | 88 | 31% | 3:18 |

| 2005 | 256 | 295 | 1.2 | 92 | 31% | 3:16 |

| 2006 | 256 | 311 | 1.2 | 107 | 34% | 2:37 |

| 2007 | 256 | 327 | 1.3 | 122 | 37% | 2:38 |

| 2008 | 256 | 315 | 1.2 | 117 | 37% | 2:40 |

| 2009 | 256 | 328 | 1.3 | 126 | 38% | 2:39 |

| 2010 | 256 | 361 | 1.4 | 133 | 37% | 2:42 |

| 2011 | 256 | 390 | 1.5 | 172 | 44% | 2:30 |

| 2012 | 256 | 435 | 1.7 | 170 | 39% | 2:33 |

| 2013 | 256 | 423 | 1.7 | 185 | 44% | 2:25 |

| 2014 | 256 | 439 | 1.7 | 151 | 34% | 2:13 |

| 2015 | 256 | 415 | 1.6 | 176 | 42% | 2:16 |

| 2016 | 256 | 345 | 1.4 | 149 | 43% | 2:25 |

| 2017 | 256 | 429 | 1.7 | 196 | 46% | 1:44 |

| 2018 | 256 | 349 | 1.4 | 172 | 49% | 2:01 |

| 2019 | 256 | 417 | 1.6 | 196 | 47% | 2:08 |

| 2020 | 256 | 364 | 1.4 | 198 | 54% | 2:26 |

| 2021 | 272 | 279 | 1.03 | 158 | 57% | 2:23 |

| 2022 | 271 | 283 | 1.04 | 164 | 58% | 2:25 |

| 1999- 2022 | 6,151 | 8,037 | 1.31 | 3,262 | 40% | 2:38 |

Chicago Bears president Ted Phillips said after the successful 1999 vote, “We don’t know if it’s the perfect system.”

The perfect system? The NFL may never find the perfect system. But each year, instant replay improves dramatically. Technology has helped the league come a long way — from stopwatches, walkie-talkies and pagers. And technology will continue to improve the process, allowing the league to make rulings correctly and consistently.