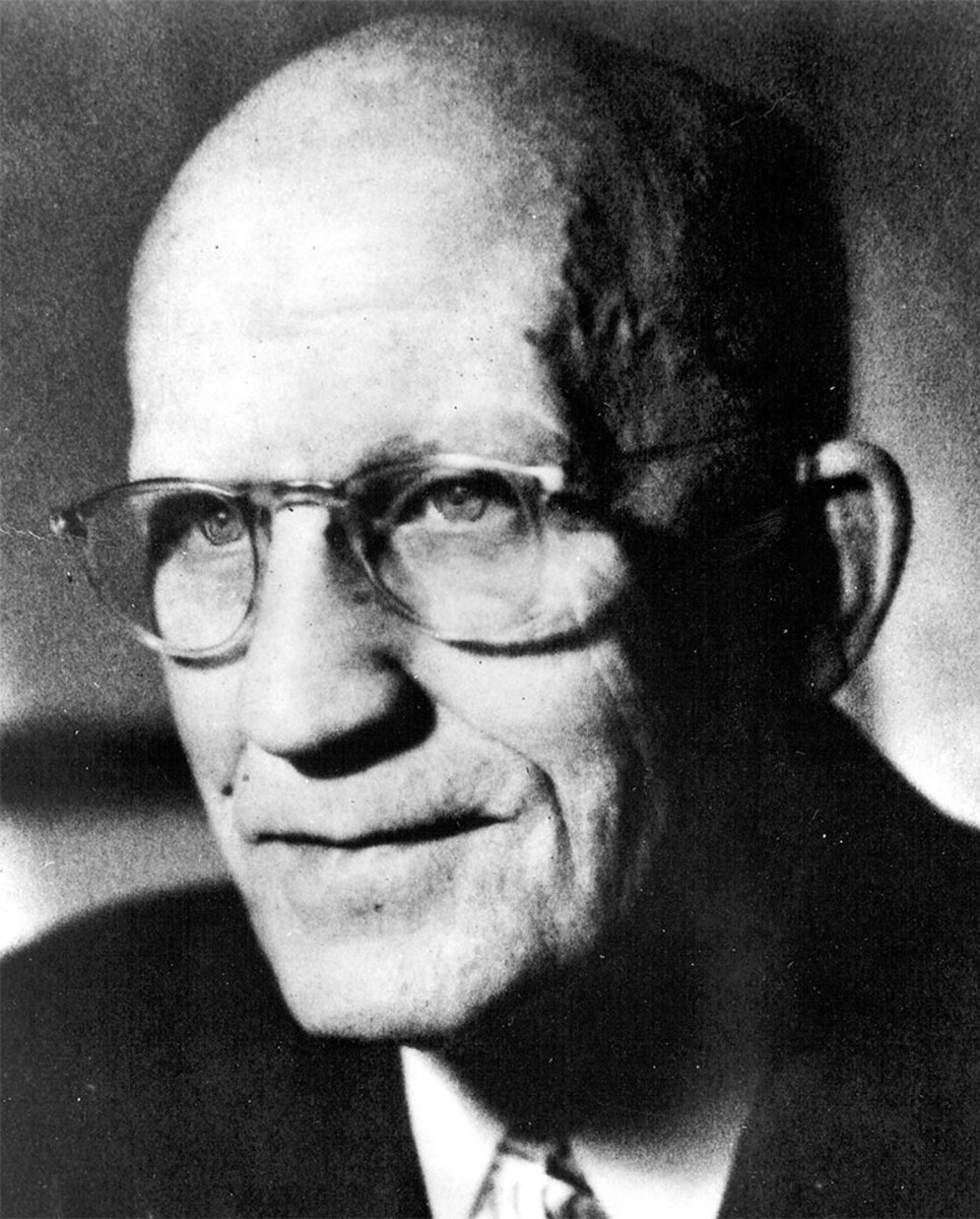

Hugh “Shorty” Ray

NFL Supervisor of Officials, 1938–1952

Though he was only 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighed just 136 pounds, Hugh “Shorty” Ray had an outsized influence on professional football. The only NFL official to be named to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Ray used science and statistics to improve officiating, reform the rules and make the game more exciting for fans.

Getting the league to hire 'Shorty' Ray was my finest contribution to pro football. — George Halas, Hall of Fame coach

Ray, a multisport athlete in high school and at the University of Illinois, told a Chicago Sun-Times reporter in 1946 that he became interested in rules during his playing days in the early 1900s. That’s because his athletic director and baseball coach, George Huff, insisted that all the players be well-versed in them.

(AP/Pro Football Hall of Fame)

After college, Ray taught mechanical drawing in high school in Chicago for more than 30 years. He also coached football and baseball and officiated football, baseball and basketball games for the better part of three decades. That experience fed his desire to take a leading role in improving how officials were trained and how football’s rules were crafted.

The NFL hired Ray in 1938 at the urging of legendary Chicago Bears coach George Halas, who had noticed his work with high school sports associations, including one he had formed in Chicago to oversee and improve officiating. Brought on as a “technical advisor,” Ray quickly set about mastering the way the pro game was played. Often seen with a stopwatch, pencil and slide rule, he made more than 300,000 technical observations, according to the Hall of Fame. Learn how Shorty’s methods changed the game.

“Ray’s scientific approach to the game prevented coaches from obtaining rule changes solely for their own benefit,” Halas said in 1974. “He generally ensured that any rule changes would be solely for the benefit of the entire league and in the interest of the fans.”

Ray knew that an improved rulebook was meaningless if it was poorly or inconsistently enforced, and he demanded officiating excellence to reinforce the integrity of the game.

He required officials to learn the rules forward and backward, and he tested them on their proficiency. He created tools to improve officiating techniques and mechanics, including the first “play situation book,” which prepared officials to make the correct call in most conceivable scenarios. The NFL’s Officiating Department uses a similar book today.

At the time of Ray’s death in 1956 at age 71, few knew of his revolutionizing effect on professional football. That changed a decade later, when he was enshrined in the Hall of Fame.